ASHEBORO, N.C. (ACME NEWS) — It was 56 years ago this month that two American astronauts became the first humans to walk on the moon—a feat made possible thanks not only to thousands of humans, but also a cheerful, wrinkle-faced chimpanzee named Ham who called the N.C. Zoo home for several years.

The Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union intensified in 1957, when the USSR launched Sputnik 1 — the world’s first artificial satellite. Just a month later, Sputnik 2 carried a dog named Laika, making her the first animal to orbit Earth. By early 1959, the Soviets upped the ante again with Luna 1, the first spacecraft to escape Earth’s gravity and pass near the Moon.

In 1959, Dwight D. Eisenhower was president, Alaska and Hawaii had just become the 49th and 50th states, and the Cold War loomed large with the ever-present threat of nuclear annihilation. Soviet space achievements — though framed as scientific milestones — were widely viewed in the U.S. as demonstrations of military capability, suggesting the USSR could deliver nuclear weapons across continents. With America seen as falling behind, the Space Race became more than a contest of exploration. It was a Cold War clash of ideologies — capitalism versus communism — and a strategic battle for control of the high ground of space.

NASA at this point is barely a year old. The next milestone in the space race, and one of the agency’s first goals, is to get a human into space, and back —but scientists didn’t yet know if the human body could survive the rigors of launch, weightlessness, and reentry. To answer this question, they turned to chimpanzees due to both their intelligence, physiology, and reflexes remarkably similar to our own.

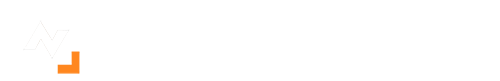

Ham’s Journey

Ham, born in July 1957 in French Cameroon, was captured as an infant and brought to the Rare Bird Farm in Miami, Florida. In 1959 he was sold to the Air Force for $457 and sent to Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.

Over the next 18 months, Ham, known only as “No. 65” to avoid the bad press that would come from the death of a “named” chimpanzee if the mission were a failure, underwent 219 hours of training to learn to do simple, timed tasks. He was taught to push a lever within five seconds of seeing a flashing blue light; failure to do so resulted in an application of a light electric shock to the soles of his feet, while a correct response earned him a banana pellet.

Ham was selected for the Mercury-Redstone 2 mission and on January 31, 1961, Ham was suited up, strapped into a special flight chair, and placed in the capsule atop a Redstone rocket at Cape Canaveral, in Florida.

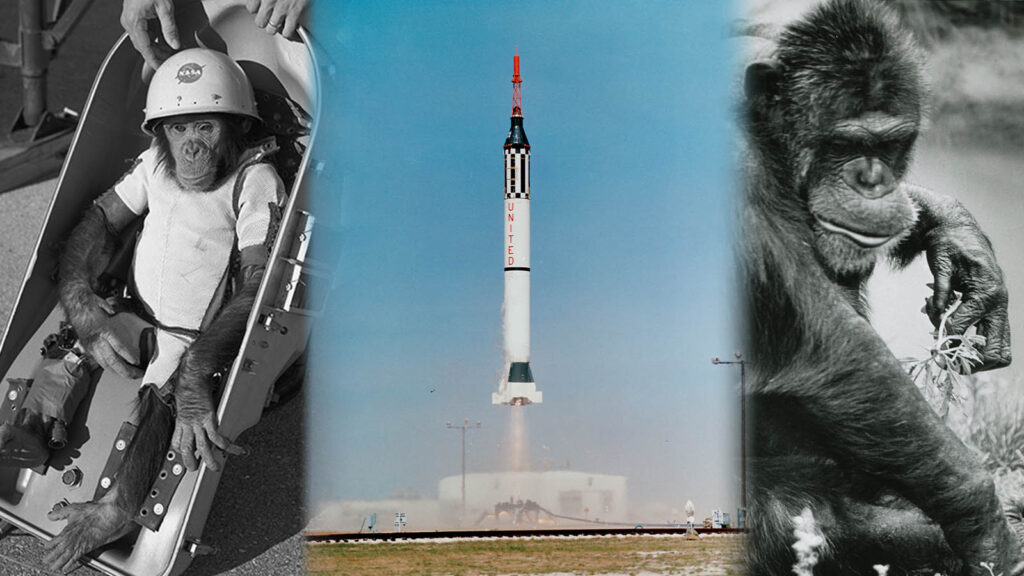

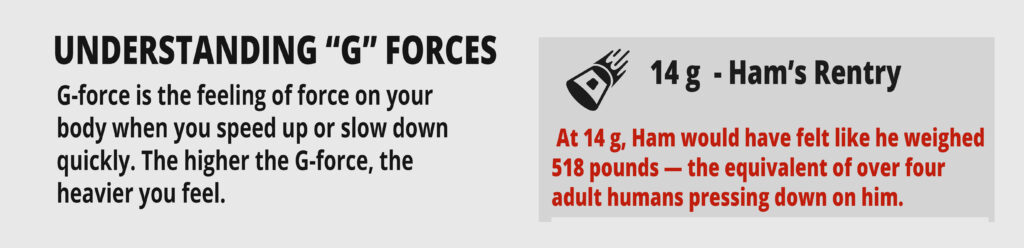

The 16 minutes and 39 second flight did not go as planned. A valve malfunction triggered the emergency escape rocket, subjecting Ham to 17 g’s of acceleration. At the peak of the flight, Ham experienced six and a half minutes of zero gravity, before excessive speed and a prematurely jettisoned retro rocket pack resulted in 14.7 g on reentry. A loss of cabin pressure and a rough splashdown off course all added to the danger.

Ham was recovered from the Atlantic Ocean by the USS Donner. He emerged hungry but healthy—and became the first hominid in space. A post flight examination found a small abrasion on the bridge of his nose and noted he was dehydrated having lost just over 5% of his body weight.

Despite the chaos and extreme forces, Ham performed his tasks only a fraction of a second slower than on Earth. Scientists recorded only two shocks, one from a malfunction, the other due to no response shortly after pulling 14g during reentry.

Even though the rocket had experienced problems, Ham had accomplished his mission. The results from his test flight led directly to Alan Shepard’s May 5, 1961, suborbital flight aboard Freedom 7.

Ham became a national celebrity, retired from NASA, and moved to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., in 1963. There, he lived for 17 years, pampered by zookeepers and beloved by the public.

In 1980, he joined a small troop of chimps at the North Carolina Zoo.

He died there only three years later on January 19, 1983 at the age of 25, from complications from chronic heart and liver disease. While controversy surrounded the handling of his remains—his skeleton preserved for study and his soft tissues were cremated. Ham’s grave now lies beneath a bronze plaque at the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico.

###