ASHEBORO, N.C. (ACME NEWS) — The Randolph County Sheriff’s Office is one of nearly 30 North Carolina agencies participating in a federal partnership with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement—also known as ICE—that allows local law enforcement to assist in certain immigration duties.

Known as the 287(g) program, it’s one of ICE’s key partnerships with local agencies with more than 1,000 law enforcement agencies participating nationwide. Supporters say it improves coordination between local jails and federal immigration authorities, while critics argue it blurs the line between local policing and federal enforcement.

What Is the 287(g) Program?

Congress created Section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1996. It authorizes ICE to train and certify state and local law-enforcement officers to perform certain immigration functions under ICE oversight.

According to ICE, the program “enhances the safety and security of our nation’s communities” by allowing local law enforcement to identify and transfer custody of individuals who are in the country unlawfully and have been charged with or convicted of crimes.

ICE operates three models of 287(g):

- Jail Enforcement: Used to identify and process removable non-citizens who are already in local custody.

- Task Force Model: Allows certified officers to assist ICE during routine police duties in the field.

- Warrant Service Officer Program: Authorizes jail officers to serve and execute ICE administrative warrants and removal orders within their detention facilities.

Randolph County participates in the Warrant Service Officer program, the most limited version.

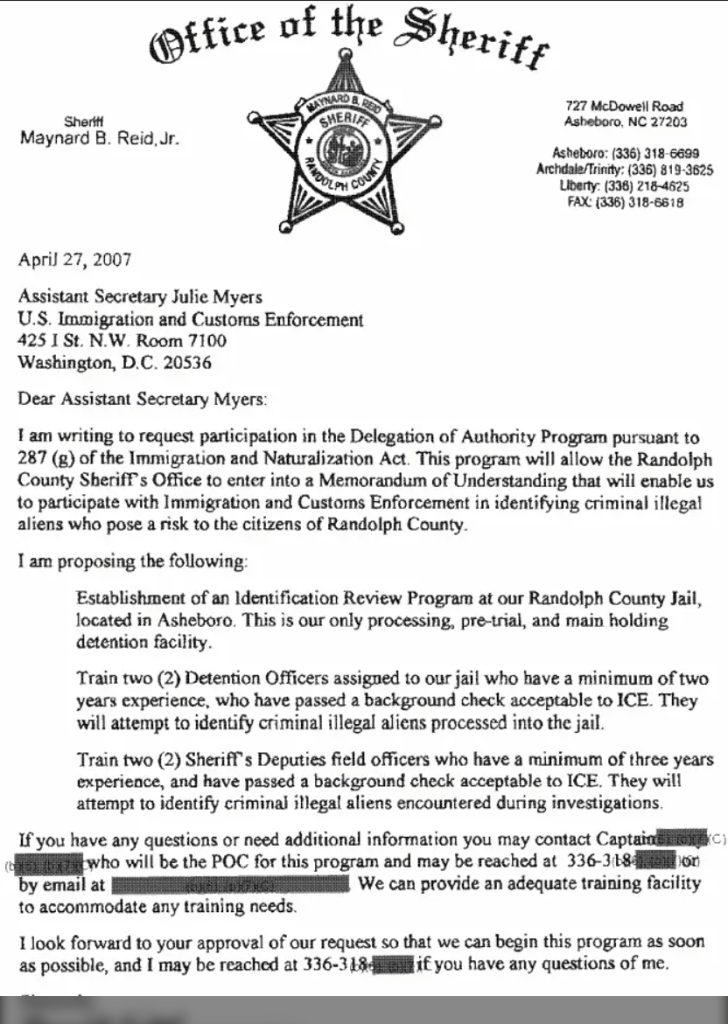

Randolph County’s Agreement

The Randolph County Sheriff’s Office first expressed interest in joining the 287(g) program on April 27, 2007, when then-Sheriff Maynard B. Reid, Jr. sent a letter to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Washington, D.C. The letter proposed creating an Identification Review Program at the county jail in Asheboro and training a small group of detention officers and deputies to help ICE identify inmates who might be in the country illegally.

While records are unclear about what followed that initial inquiry, the Randolph County Sheriff’s Office formally entered the program in the following years. On May 21, 2020, Sheriff Greg Seabolt signed a Warrant Service Officer agreement with ICE — the county’s current and active 287(g) memorandum.

Under the agreement, trained and certified deputies may serve and execute ICE administrative warrants for immigration violations and warrants of removal or deportation, but only inside the county jail. Their authority under the MOU applies solely to inmates already in custody at the jail on state or local charges. When an inmate is scheduled for release, deputies may coordinate with ICE to transfer that person into federal custody if ICE issues a detainer. Such transfers must occur within 48 hours of the scheduled release and following federal rules.

An ICE administrative warrant is not the same as a criminal arrest warrant. Unlike a judicial warrant, which is signed by a judge, an administrative warrant is signed by an ICE official and authorizes the arrest of a person suspected of violating federal immigration law.

These powers apply only to inmates already charged with state or local offenses and only inside the county jail. The sheriff’s office reports one certified deputy currently trained and authorized under the program.

Randolph County deputies cannot conduct immigration enforcement in the community. The agreement does not authorize immigration arrests outside the jail, workplace or neighborhood “raids,” or questioning people about immigration status during patrols. All activity must occur within the jail and only at the time of an inmate’s release.

Randolph County also covers its own costs — including salaries, overtime, and training or travel — while ICE provides instructors, materials, and access to databases. There is no reimbursement for local expenses unless a separate detention agreement exists.

North Carolina Context

As of late 2025, 27 law-enforcement agencies in North Carolina participate in the 287(g) program, including Cabarrus, Gaston, Henderson, Alamance, and Randolph counties.

ICE’s monthly reports for 2025 list enforcement in several counties in N.C. through the program involving charges such as drug trafficking, sexual offenses, and reentry after deportation. However, the report says that its data is a “sampling of criminal aliens recently identified by state or local law enforcement operating under the 287(g) Program,” indicating it’s not a complete record.

Randolph County has not been cited in any of those reports this year. When asked how many times ICE had requested deputies to serve administrative warrants or removal orders at the Randolph County Jail, the sheriff’s office said it could not provide that information under the terms of its agreement with ICE. The office directed inquiries to ICE’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) process for records of such requests.

Bottom Line

Supporters say the 287(g) program helps close gaps between local and federal enforcement, ensuring that individuals charged with serious crimes are transferred to ICE custody. Critics argue that even limited participation can create confusion, raise concerns about profiling, and distance local agencies from the communities they serve.

For Randolph County, the partnership’s reach stops at the jail door. Deputies serve paperwork, not warrants in the field — carrying out a narrow role that connects the local jail to a much larger federal immigration system.

###