ASHEBORO, N.C. (ACME NEWS) — Nearly 20 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, AL, a schoolteacher named Vella Lassiter staged her own act of defiance in Asheboro.

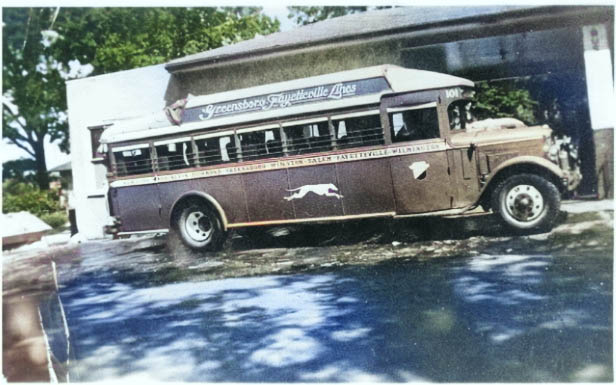

On Easter Monday, March 29, 1937, 41-year-old Vella Lassiter—also known as “Miss Vellie”—boarded Bus 103 at the Fayetteville Street station in Asheboro following a weekend visiting family. A respected educator and Bennett College graduate, Lassiter was starting the first leg of her commute to Washington Street School in Reidsville. Because of heavy holiday travel, the rear section reserved for Black passengers was full, leading Lassiter to take a seat in the next available row beside a white woman.

Before the bus moved an inch, the driver, C.L. Bowman ordered Lassiter to move in what court records later described as a “mean tone.” Lassiter refused to budge, telling the driver she had purchased a ticket and was “just as good as any white person on this bus.”

The incident escalated when local Asheboro Police Officer Pearly Miller attempted to lead Lassiter by the arm down the aisle. When she refused to move her feet, Officer Miller was forced to drag her. At the door, Lassiter gripped a support pole so tightly that a second officer, Zeb Keever, had to pull her arm while Officer Miller pried her fingers away one by one.

Following the struggle, Lassiter was left on the sidewalk in tears. She had suffered a stretched nerve in her shoulder and arm in the struggle —injuries that would eventually form the basis of her lawsuit against the Greensboro-Fayetteville Bus Line.

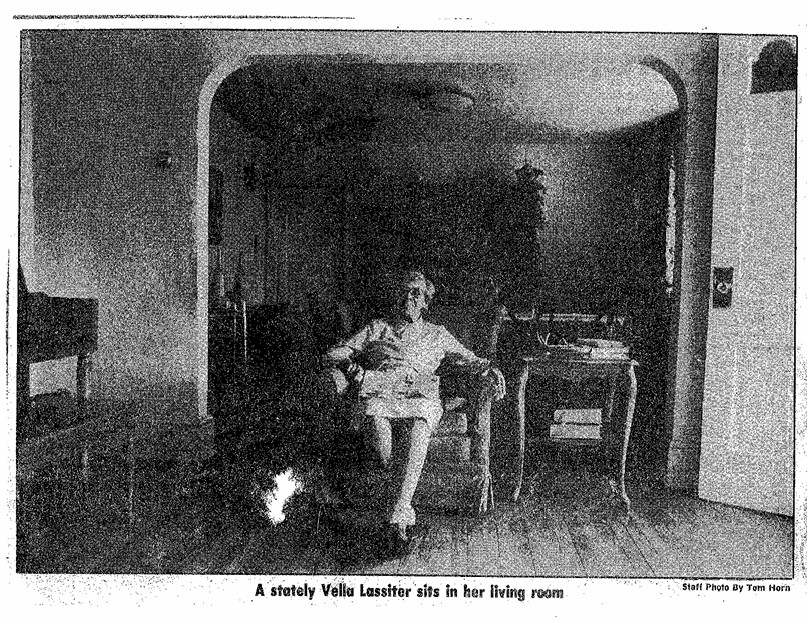

“I was kind of stubborn about having to get off,” Lassiter told a reporter in 1985. Her cousin later joked in the same interview that Lassiter maintained that same firm grip well into her 90s.

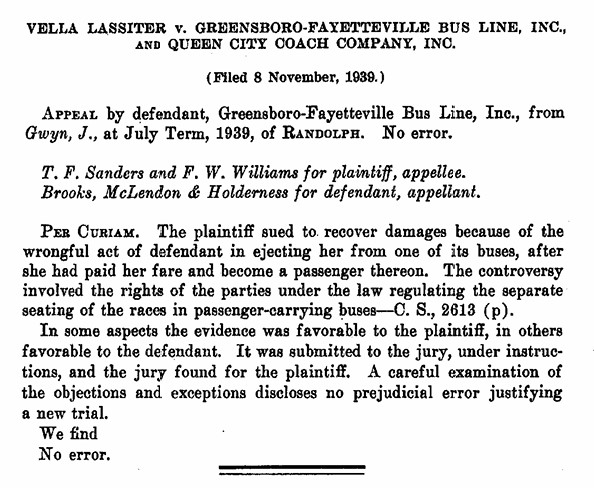

Led by her cousin T.F. Sanders and attorney F.W. Williams, Lassiter’s legal team argued a “breach of contract” rather than challenging the constitutionality of segregation. This was a tactical move; in 1937, North Carolina law explicitly mandated separate seating for Black and white passengers and gave bus lines and police the authority to enforce those rules.

The argument was straightforward: Lassiter’s lawyer contended that by accepting her 45-cent fare, the bus company entered into a legal contract and was obligated to provide her with safe transportation to her destination.

The trial, held in Randolph County Superior Court, saw an unusual display of interracial support. Despite the social climate of the 1930s, both Black and white residents of Randolph County testified as character witnesses on Lassiter’s behalf.

In July 1939, a local jury ruled in Lassiter’s favor, awarding her $300 in damages—a significant sum at the time, equivalent to approximately $6,600 today. The bus company appealed the decision, but the North Carolina Supreme Court upheld the verdict in November 1939.

Lassiter’s boldness was rooted in a deep family history of independence. Her ancestors were free landowners as far back as the 1770s. Her great-grandfather became one of the first Black Quakers in the South after being accepted into Randolph County’s Back Creek congregation in 1845. This financial and social independence allowed the Lassiter family to resist the economic retaliation that silenced many other voices during the era.

While Lassiter’s victory did not dismantle the statewide segregation system, its immediate impact was felt on the local lines. Kate Jones told the News & Record in 1999 that following the lawsuit, Black riders—at least on that specific bus route—began sitting toward the front while drivers remained silent, likely fearing further legal action.

Historians like UNC-Chapel Hill professor Joel Williamson view her case as a critical precursor to the organized movement of the 1950s. “She was part and parcel of an attitude that said, ‘We’re not going to take this,'” Williamson said in a 1999 interview. “That’s the attitude that brought down segregation. It took all those tiny little hits”. Despite this significance, the case remained largely obscured; in 1999, 12 historians, including experts on North Carolina civil rights, admitted they knew nothing about Lassiter’s case when contacted by the News & Record.

Lassiter continued her career in education, teaching for 40 years before passing away in 1994 at the age of 99. Lassiter’s story was only recently highlighted, as in 1999 when the News & Record was writing an article about Lassiter, 12 separate local historians were unaware of her at the time.

Novella Ann “Vella” Lassiter, passed away at age 99 in 1994. She is buried at the Strieby Congregational United Church of Christ Cemetery in Asheboro.

Today, as Randolph County observes Black History Month, her story serves as a reminder that the road to civil rights was paved by individual acts of courage long before they became national headlines.

—

This article would not have been possible without assistance and the work of the Randolph Room at the Asheboro Public Library. Find out more at https://randolphlibrary.libguides.com/c.php?g=710731

###